News

- February 2014

- A Lunch with Mavis

- December 2013

- Award Season

- November 2013

- Harper's Magazine and The Wall Street Journal

- September 2013

- Interviews and Reviews

- August 2013

- Live on NBC's 'Morning Joe'

- Excerpts and Other Reading Material

- Book Launch!

- July 2013

- Charting

- An Excerpt

- The Trades Are Glowing

- Dreaming of Forever

- June 2013

- The Wylie Agency

- Limited Edition Octopus Print

- November 2012

- On The Big Screen

- Fruit Hunters on Dr. Oz

- China, Japan, Korea

- February 2011

- A Few Recent Stories

- Wall Street Jam

- Tomatoes and Kids

- Travel and Leisure

- October 2009

- "The Very Noble Train of the Huntsman"

- CBC Book Club And Other News

- September 2009

- Goblin Market

- A Bumper Crop...

- Turning Japanese

- August 2009

- The Children of Light - Photos!

- Get Fruity

- The Eternal Ones of the Dream

- June 2009

- UK Fruit Media Blitz

- May 2009

- Fruits of Desire

- The Fruit Hunters UK... and other editions out now!

- April 2009

- Newsflash: The Center of the Galaxy Tastes Like Raspberries

- Systems of Delayed Orgasms...

- Obsession Lesson

- March 2009

- More Mega-Fruit Coverage

- January 2009

- Reading Matter

- Upcoming Engagements

- Miracle Fruit Frenzy Continues!

- October 2008

- Shortlisted 2x, Readings...

- Fruit Club!

- Morphology, Purple Flowers

- Audio Book

- Interviews, etc

- July 2008

- Maslin Picks Fruit!

- Montreal Miracle Fruit Party

- Fruity Freakies

- June 2008

- Montreal Launch

- May 2008

- New York Times Hearts Fruit Hunters

- Canadian Tour

- Jerusalem In My Heart

- West Coast

- A New Fruit Hunter Blog

- Q&A

- Utne Reader on Orion Excerpt

- Pre-Publication Fruit Hype

- “Baby, Let’s Make Fruit Salad”

- April 2008

- Fruit Tour

- The City is Blue

- The Trades Are Glowing

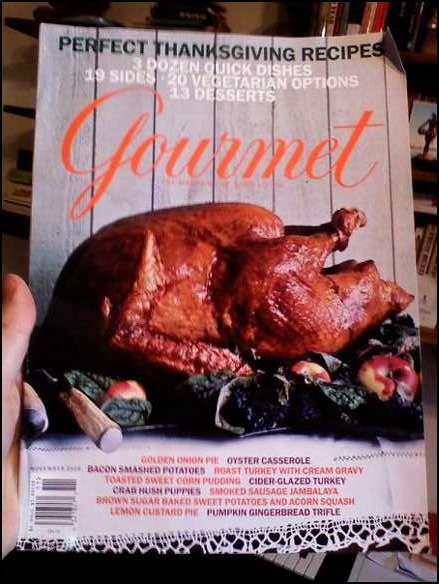

"The Very Noble Train of the Huntsman"

Oct 15, 2009So the final issue of Gourmet Magazine (ever?) just arrived.

I opened it up…

And, yes, my story “The Very Noble Train of the Huntsman” happens to be in it.

Read on…

THE VERY NOBLE TRAIN OF THE HUNTSMAN

A sweep of green infinity unfurled outside the train window: endless trees and mountains, rivers the color of Coca-Cola. I was in the midst of being hypnotized by the sheen of water glistening on a rock face when I felt someone tap my floppy fishing hat.“We’re getting coffee,” said Frédéric Morin, chef and co-owner of Montreal’s Joe Beef restaurant. His co-chef and fellow restaurateur, David McMillan, was already at the kitchenette at the rear of the train. Gazing at the painting of a moose silhouette on the wall next to McMillan was Robert Pobi, an antiques dealer and aspiring novelist who describes his current manuscript as the “next great American angling novel.” I headed down the aisle behind Kim Côté, a young farmer and chef from Kamouraska who moonlights as a professional guide on $1,500-an-hour helicopter caribou hunts.

The five of us were hundreds of miles from home, chugging through the mossy hinterland of northern Quebec. The steel blue seats and gray interior of this two-car train were straight out of the 1940s. So was its cheery stewardess, clad in a starched navy blue uniform and silk ascot. It was clear from our equipment that we were on a fishing trip, but she suspected that we weren’t her typical passengers. “Have you ever been this far north?” she asked, doling out a round of Styrofoam cups.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been beyond my cellphone range before,” McMillan replied.Not being a big fan of filtered coffee, I asked for a short espresso. The attendant’s smile faded. She looked me over with a mixture of pity and bemusement, her gaze lingering for a moment on my brand-new, crisply pleated Wrangler “angler” pants.

“We don’t have espresso,” she said acidly. “This is a train for hunters and fishermen.”Forget macchiatos. VIA Rail’s Abitibi line barely has stations. Passengers taking this fall journey make reservations to detrain at any number of unmarked spots near their outfitters; on the way home, they simply flag down the train and head back with their catch. Morin refers to it as “The Very Noble Train of the Huntsman.” The spine of Quebec’s wilderness sporting country, it curves through what VIA calls a “vast hunting, fishing and outdoor adventure territory encompassing 460 km of railway.”

Prior to the railroad’s construction in the late 19th century, the only way to get up here was by canoe. Storied pioneers—nomadic, beaver-trapping, French fur traders known as coureurs de bois (woods runners)—used to roam the area with nothing but a pot of lard, some dried berries, and maybe a moose muzzle on lucky nights. They were living off the land, just as the First Nations did for millennia before Europeans arrived.Settlers started building private hunting and fishing clubs as the tracks were being laid. They hacked their way through the forest primeval, naming lakes and inventing dishes like Biscuits à la Gregory (sailor biscuits cooked in bacon grease and topped with marmalade). The American painter Winslow Homer, an early and repeat visitor, said Quebec had the best fishing he’d ever encountered. By the late 1800s, gentlemen anglers from the United States and Europe were packing the railcars. Photos from the era show dapper sportsmen in fancy boots and cravats reclining while smoking cigars. Although train traffic has waned with the rise of air travel and SUVs, the Abitibi line continues to haul trophy antlers and wild venison through the countryside.

A month before we set out, I was looking at Joe Beef’s chalkboard menu and asked Morin about a dish called Dining Car Calf Liver. He told me that the recipe came from an old Canadian National Rail training manual for chefs. “During the golden age of rail travel, trains used to serve haute cuisine on fine china,” he explained. “My thing is food on trains.” Beneath the lanterns on his restaurant’s outdoor patio, he rhapsodized about how you see landscapes on the train you’d never see in a car. “You know, its beautiful to see the highway 20 out your window when you are plastered on Canadian Merlot.”

A self-proclaimed train-freak, Morin carries a VIA Railways timetable with him at all times. He started thumbing through the schedule to plan the trip we had agreed to take. Searching for hunting and fishing stations close to the end of the line, he settled on Club Kapitachuan, an 11-hour ride away. Because it’s so remote, there would likely be pristine fishing and, most importantly, ample time to enjoy his beloved train.

Most of Montreal’s finest restaurants tap into the mythology of the well-fed outdoorsman, whether it’s the “man-sized French Canadian cooking” of Martin Picard’s Au Pied de Cochon or of Old Montreal’s Le Club Chasse et Pêche, named after northern sporting lodges and decorated in kind. These restaurants, like the institutions they revere, are temples of hedonism. It’s as though overindulgence became a way of compensating for—or obliterating the memory of—the hardships endured by the coureurs de bois. As early as the 19th century, sporting periodicals were already describing larders bulging with baskets of Champagne, magnums of claret, a “fair allowance” of dry Sherry, barrels of India Pale Ale, and cases of “eau de vie pale et vieille for medicinal purposes.”

Morin and McMillan grasped this intuitively. When I’d stopped by a few days before our trip, waitress Meredith Erickson told me they’d been arguing about how much wine to bring: 72 bottles or 84 bottles? I did the math: the five of us would each need to drink around four bottles per night. Erickson looked at me with sympathy: “I hope they don’t get too Deliverance on your ass.”

On the morning of our departure, the agent said he hadn’t printed tickets to Kapitachuan in the 37 years he’d worked at VIA. “It’s what they call a flag stop,” he said. “There’s just two poles in the ground. You’re right in the bush. There’s no electricity. You hear the wolves at night. The lakes are full of fish. It’s paradise.”

*

Morin had been in paradise from the moment we boarded the noble train in Montreal. Adjusting his striped railway engineer’s cap, he called our attention to “the romance of the bells tolling.” The stewardess forgot about my coffee gaffe, and we drank train-issued Merlot from individual juice boxes. Across the aisle was a rotund, gray-haired hunter who gave us a recipe for beaver tails “more tender than scallops.” (Boil them three times and then cook with bacon and butter. Otherwise, he warned, “They’ll just taste like oily aspen trees.”) We coasted through places like Grand-Mère, where the nearby mountain resembles a grandmother’s head, and Windigo Station, named after the mythical Algonquin creature said to have an insatiable appetite for human flesh. We glimpsed a large tepee, seemingly still in use.

It was dark by the time we arrived. Our outfitters picked us up at the flag stop and drove us through the dirt-road night. They were the manliest men we’d ever seen, with Tom of Finland hair-cuts, lumberjack shirts, and meaty hands the size of baseball mitts. They spoke in supernaturally deep voices, warning that we’d be competing for fish with an abundance of black bears. Our main quarry was the northern pike, a needle-toothed water wolf known to devour entire geese or dogs and to bite chunks out of canoe paddles. We’d also be trolling for walleye, a delicious aquatic tyrant whose mohawk of spines can stab through unsuspecting hands. There was even a chance that we’d catch ouananiches, fearsome combatants characterized by old-timers as “the bravest warrior of all creatures that swim.”

As we lifted our gear from the pickup truck, our senses tingled from the forest perfumes. Our cabin was sparsely furnished but had everything we needed: a table and chairs, beds, a fridge and a wood-burning oven. The club was three hours away from the nearest grocery store, so we’d packed all our victuals for the next five days. That meant bringing an entire side of bacon, a sack of potatoes, garlic cheese grits from South Carolina, and Puy lentils instead of the traditional fèves au lard (a classic Quebecois breakfast dish of baked brown beans with bacon fat and either molasses or maple syrup). McMillan began by unpacking the cases of wine. Côté hoisted the lid off a cooler full of guinea hens and pork thighs he’d raised on his farm. Alongside Côté’s meats, we’d be eating a panoply of flesh, including rabbit, beef tenderloin, and a pork and prune fricassee topped with unwieldy portions of foie gras from Joe Beef. “As they say: sinful,” winked Morin.

Periodically rubbing the small tattoo of a carrot on his shoulder, Morin fried up Côté’s guinea hens in cast-iron pans. McMillan uncorked premier cru Volnays and prepared a crisp, bubbling potato dish he’d been taught to make by the monks of Notre-Dame de Cîteaux, a Cistercian abbey in Burgundy. It was a gratin dauphinois type of concoction with a few secret ingredients: browned chicken wings, ham hocks, and cheese from the abbey. He placed the potatoes on top like a deck of fanned cards. After baking the dish, he broiled it so that the tips of each potato slice turned golden-brown while the interior remained a gooey mess. As they say: sinful. A day of fishing ahead of us, we fell asleep full and happy. A chamber orchestra of snoring soon filled the room.

*

The following morning, we showered in freezing water and then headed out in motorboats. We drifted around, idly pitching our lures into the depths. Morin spoke about the way time seems different on a train—and when fishing out on the lake. I was learning what he likes to call “the lessons of the teachings.” Steam curled above unrippled black pools. Daggers of sunlight carved holes in the clouds. “See those reeds there?” exclaimed Pobi at one point, gesturing toward some bog myrtle. “I guarantee you there’s a monster pike in there with its gills flaring open, waiting to eat.” And indeed there was. McMillan fought hard to reel in an iridescent beast whose maw snapped at us with what seemed like thousands of razor-sharp teeth. One after another, we brought in walleye and pike the likes of which I’d never seen before.

The days evaporated in a meditative trance. There was a lot of storytelling, joking, and competition over who could catch the biggest fish. The winner was Bobby Moore, our Cree guide. The odds were in his favor: He’d been fishing these lakes since 1972. “How amazing that there are still native guides who know the water and the land,” Morin marveled.

As we drifted through the wide-open beauty of rural Quebec, Moore pointed out mink scampering into the pines and eagles circling overhead. Burly black bears hightailed it whenever they heard us approaching. Our boats brought us deeper and deeper into the wilderness, each new lake as still as a mirror. “It’s like this until the Arctic Circle,” Moore said. “The trees get smaller and smaller until you finally hit the tundra.”

“Once you’ve seen the tundra, you don’t want to come back,” added Côté. “It’s fields of blueberries and cranberries all the way to the horizon.”We caught so many fish that hunting would have been pointless. We didn’t end up having Moore’s special “shore lunch,” which consists of walleye deep-fried in shortening. (“It’s hard on the arteries, but everybody likes it.”) Instead, McMillan and Morin baked buttered walleye fillets in a Le Creuset gratin dish they’d found in a junk store before pulling out of Montreal’s Central Station. Over lunch, Moore told us that moose meat doesn’t taste good—although he and Côté agreed that reindeer is maudit bon (cursedly delicious).

We ended each day with meals as simple as they were unforgettable. Morin covered the massive tenderloin with coriander seeds and cooked it over an open fire he’d built outdoors. Watching him work, I learned that everything goes better with mustard and bacon. Morin explained that he operates according to the “Big Mac theory,” the idea that each mouthful should be “sweet, creamy, salty, fatty, smoky, and umami all at the same time.” His food activates all your taste buds, through whatever means necessary, including ingredients many “serious” chefs might sniff at. He uses crushed potato chips as a garnish and cooks with heads of ornamental chard or cabbage his sous-chefs sometimes steal from city parks. (It’s his signature prank.) He recommends marinating meats in no-name supermarket salad dressing and will greet guests at the bar with a just-deep-fried lobster Montecristo sandwich. Melding high and low in almost preposterous ways, he likes to stuff éclair buns with lobes of foie gras and Velveeta. I’ve dropped into Joe Beef’s backyard to find him smoking fish inside a tin garbage can or cooking omelets in a wheelbarrow.

At least one serious chef—David Chang, of New York’s illustrious Momofuku—understands: “There’s no rhyme or reason to their menu—it’s whatever they want to do—and God bless them for that,” he told me just before our trip. Chang, who recently spent four consecutive nights eating at Joe Beef, also said: “There’s nowhere in the world like it. It’s one of my favorite places of all time.” Morin and McMillan’s food is even better in the woods. One night, after eating eight homemade sausages each, we had rabbit stew, mashed potatoes, and lentils, which we ate with bottle after bottle of wines from Alsace, Jura, and Graves. As we feasted, we listened to shortwave radio. Morin spoke about his penchant for food in unexpected places. “I’d like to fill the city’s birdbaths with shrimp cocktails,” he pontificated, opening another bottle of dry Sherry. “We should set up three tables in the abandoned green space beside an old church whose doors are always locked. People could eat in the tall grass behind a wrought-iron fence.”

After a final night in the snoretex, we said good-bye to our outfitters and Bobby Moore, flagged down the train, and clambered aboard. A few hours later, the conductor let us disembark while we waited for a freight train to pass. We found ourselves in a misty timber yard, surrounded by thousands of enormous logs stacked like a giant’s toothpicks. We were poised between nature and civilization, woodsmen returning home.

“Listen,” Morin said, tilting his head. Our noble train was throbbing, humming, clicking, purring, exhaling, digesting. The oncoming train’s horn pierced the fog. “This is magnificent,” Morin murmured. The freight train whooshed by us, trailing a bouquet of diesel fumes and wood chips. Our conductor blew his whistle. We took a last glance at the forest primeval and hopped back on to our train. It coughed a few times, composed itself, and then set off regally for downtown Montreal. ◊